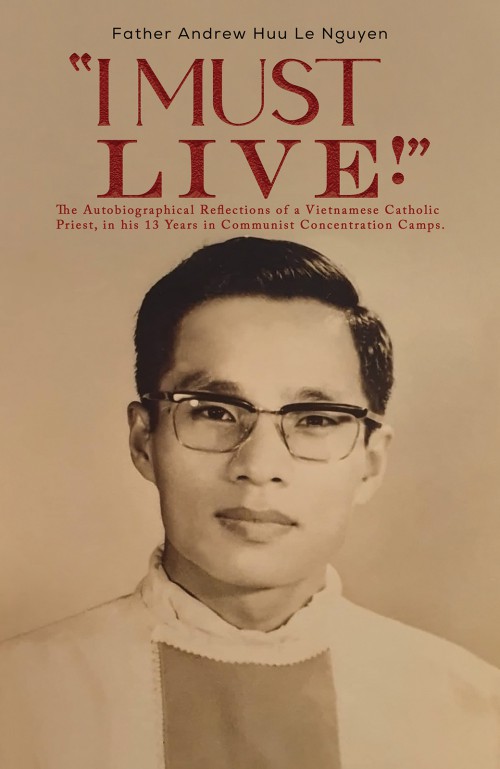

"I Must Live!"

On April 30th 1975, South Vietnam fell into the hands of the Communists from the North. Countless Southerners from various backgrounds were being herded into concentration camps. The author was one of them.

“I MUST LIVE!” was the loudest scream I had ever made, which activated my survival instinct when I was tortured to the point of death. Thanks to these three words, I was able to survive in order to recount the painful and horrifying experiences to share with the readers. It was a type of experience that the readers could not possess and no one wished to have.

In short, this is my experience: Human compassion has its limits, but human evil is boundless, especially when that evil is incited and indoctrinated by the Vietnamese Communist Regime.

I hope the book I MUST LIVE! will give readers a deep insight into the darkest side of life, at the same time as to realize that they are the most fortunate people on earth compared to the life of the author.